Creating Agreements You Can Actually Understand

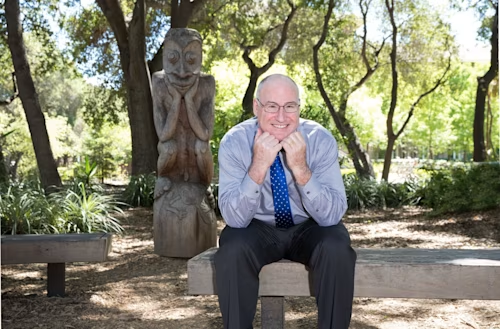

Author Bob Sutton explains how forms and agreements get ever more bloated, and how organizations become sludgy and bogged down.

Table of contents

🕒 Reading time: 7 minutes

The Art of Agreement is a series of unique perspectives from leaders and creators on the universal truths and tactics that get humans to agree. Check out the rest of the series:

Reaching Agreement with Radical Candor - featuring Kim Scott, best-selling author

The Art of Resolving Disputes - featuring Jennifer Lupo, Mediator

Using AI to Reach Agreement - featuring Martin Rand, CEO, Pactum

We’re constantly confronted with agreements that are so ridiculously long, dense, and complicated that we can’t even figure out what they say. It’s a paradox: these are agreements that actually make it harder to reach agreement. Two examples:

A state agency in Michigan made people slog through a 40-page form with 1,000 questions in order to get public assistance—and each year 2.5 million applicants endured this nightmare.

A health care provider in Rhode Island used a surgical consent form that was three pages long, and written with such lofty language that most of the 35,000 patients who signed it each year couldn’t fully comprehend what it said.

Things like this drive Bob Sutton nuts. In his new book, The Friction Project, the Stanford professor emeritus and his co-author Huggy Rao explain how forms and agreements get ever more bloated, and how organizations become sludgy and bogged down. Most importantly, Sutton explains how to be a “friction fixer.”

Key takeaways

It’s easy to make agreements complicated—and hard to make them simple.

Generative AI is a game-changer—it’s already radically improving agreements.

Sometimes adding friction is a good thing—you can slow down to move faster.

How do agreements get so huge and convoluted that you can’t understand them?

I call it “addition sickness.” We as human beings are wired such that when there's a problem to solve, we just add complexity. This applies to anything from fixing a Lego model to fixing a university—the natural tendency is to add. And then you end up with fiefdoms and more rules and more initiatives and more training. The good news is that when executives become aware of this and start to see friction, they can instill the subtraction mindset and apply specific subtraction methods. So there is some hope.

What’s a subtraction mindset?

Probably my favorite story in the book is about a guy named Michael Brennan, who became obsessed with the form that people in Michigan had to fill out to get public assistance. It had 1,000 questions and was 18,000 words long. It was more than 40 pages long. It was the longest form of its kind in the U.S., and 2.5 million people had to fill it out every year. And the questions were ridiculous. For example, “What is the date of conception of your last child?”

Mike started a firm called Civilla to work on simplifying forms like that one in Michigan. It took a long time and a lot of iteration to come up with a new form that complied with state regulations but was shorter and simpler. They tried six different prototypes in the branches. But eventually they created an agreement that satisfied all the requirements and was 80% shorter, and much easier to understand.

And that was an enormous battle. “Friction fixers” like Mike aren’t always popular.

That’s another message in the book—getting rid of friction is often a high-friction experience. Mike and the team at Civilla had to involve all the different constituencies. They had to get support from the top. There's some things that are quick and easy, but it's usually difficult. It's really hard to change anything without pissing someone off. No matter what you do, it's hard to upset people. That's why you need to build a big enough coalition to support what you're doing.

Generative AI rides to the rescue

You’re excited about the potential for ChatGPT and other generative AI systems to simplify language in agreements.

There’s a great new case study you can read about in the New England Journal of Medicine AI and the OpenAI website. The largest healthcare provider in Rhode Island, Lifespan, wanted to take this very densely worded three-page surgical consent form and make it into something that people could understand. They have 35,000 people a year signing these consent forms.

They gave ChatGPT-4 this 15-word prompt: “While preserving content and meaning, convert this consent form to the average American reading level.” The average American reads at about a sixth- or seventh-grade level, but the consent form was written at the 12th grade level. ChatGPT produced a form that’s one page long instead of three pages, and it reads at about 6th grade level. One statement was reduced from 45 words at a 12th-grade level to 19 words at a fourth-grade level.

So they’re doing two things. First, with those 35,000 people, you’re saving an enormous amount of time. But you’re also creating something that people can actually understand. If more people understand the agreement they're making, it’s more of a real agreement.

"If more people understand the agreement they're making, it’s more of a real agreement."

Sometimes it seems like agreements are made overly complicated on purpose.

One thing that we should talk about in terms of agreements is the weaponizing of them—when an organization makes an agreement that’s so long and obtuse that nobody can understand it. Suppose an organization wants to screw you. They can make an agreement as unreadable and incomprehensible as possible, to make it so difficult that people can't understand it and it's too much work to figure it out.

Tips: How to be a friction fixer

Don’t place blame. Focus on finding solutions and remedies.

Apply friction forensics. Interview people who use the agreement and solicit their ideas.

Build a coalition. You’ll need support, especially from the top, to counter resistance.

Get an assist from AI. ChatGPT is proving to be great at slicing out clutter and boiling agreements down to the bare essentials.

Going slow to go fast

You write about “good friction,” meaning there are places where it makes sense to add friction to a process inside an organization.

I love good friction. We use the example of Laszlo Bock, the former Senior Vice President of People Operations at Google. Back in the early days at Google, job candidates would go through up to 25 interviews, and then many did not get the job. But even the people who did get hired were mad at Google for making them interview so many times. It was also a burden on the Googlers who had to do the interviews.

Laszlo Bock made a rule: if more than four interviews were to be conducted with a candidate, you had to get written permission from him. Most Googlers were hesitant to do that. So just by adding that little speed bump, Laszlo sped things up. That’s an example of good friction.

Another example of good friction is a company where people were just buying apps on their own, using their credit cards. The company discovered it was paying for four different versions of Slack when they only needed one. They were paying for four or five different platforms for video meetings, such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. So they added a speed bump, saying, if you’re going to use your credit card to add an app, you have to justify it to the CEO. That’s an example of adding good friction.

One of your previous books, The No Asshole Rule, is a legendary workplace survival guide. Is it possible to reach agreement with difficult people, and if so, how?

Some people are so difficult, they're impossible to deal with. So one answer is you just give up, because the odds that you’re going to get screwed are pretty high.

But it helps to remember that all of us can be assholes under the wrong conditions—it’s more of a behavior rather than an essential quality of the person. Try to be reasonable. You might want to convey to them that given the nature of our long-term relationship, it might be better for us to work together. You appeal to their self-interest. Hopefully you can build trust.

Slow down and take time to figure out what the other person wants. Don’t start with the assumption that they're out to screw you. They may be, but it’s better to start out with trust and let them sort of show otherwise.

Dan Lyons is an author and recovering journalist who has written about technology, work and business transformation.

Related posts

Docusign IAM is the agreement platform your business needs